Pathways for Commercialising Scalable IoT Technologies

One of the most common gaps I see in the Internet of Things ecosystem is not a lack of ideas, talent, or research output. It is the gap between a working prototype and a commercially scalable product. Many IoT projects demonstrate impressive technical ingenuity in the lab but struggle to survive in real operational environments.

Over the years, working closely with IoT developers, startups, researchers, and enterprise users, I have learned to draw a clear distinction between what makes a prototype impressive and what makes a product viable. This distinction matters because the market rewards predictability far more than novelty.

I often tell young developers and researchers a simple truth: a prototype can be clever, but a commercial product must be boring. By ‘boring,’ I do not mean ‘inspiring.’ I mean predictable, stable, repeatable, and dependable. These traits enable an IoT solution to scale beyond pilots and proofs of concept.

What Commercial Scalability Really Means in IoT

Commercial scalability in IoT is not defined by how advanced the technology is. It is determined by whether the solution can be deployed repeatedly across different sites, customers, and conditions without escalating operational costs or complexity.

Scalable IoT systems behave consistently. They survive harsh environments. They integrate smoothly into existing digital workflows. Most importantly, they solve a real operational problem in a way that makes financial sense for the customer.

From an industry perspective, scalable IoT technologies tend to share three core characteristics.

Low Maintenance as a Business Requirement

The first trait is low maintenance. This is not an engineering preference. It is a business requirement.

Every time a technician visits a device, the solution’s cost increases. Travel, labour, downtime, and safety considerations all add up. In large deployments, these costs quickly overwhelm the value delivered by the data itself.

This is why energy efficiency and, increasingly, energy harvesting attract strong market interest. When devices can operate for long periods with minimal human intervention, the cost structure changes. The business model becomes sustainable rather than fragile.

Low maintenance also extends beyond power. Devices must recover gracefully from network interruptions. Firmware updates should be reliable and remote. Physical components must tolerate dust, moisture, vibration, and heat without frequent failures.

From a commercial lens, a device that works perfectly but requires frequent attention is less attractive than one that performs modestly but runs reliably for years.

Interoperability as a Survival Skill

The second trait is interoperability. The IoT world is not a clean, standardised environment. It is a mix of protocols, vendors, legacy systems, and evolving platforms.

Commercial success often goes to teams who make their solutions easy to connect rather than technically superior in isolation. Devices that expose data using standard protocols, structured payloads, and well-documented interfaces integrate faster into platforms, dashboards, and operational systems.

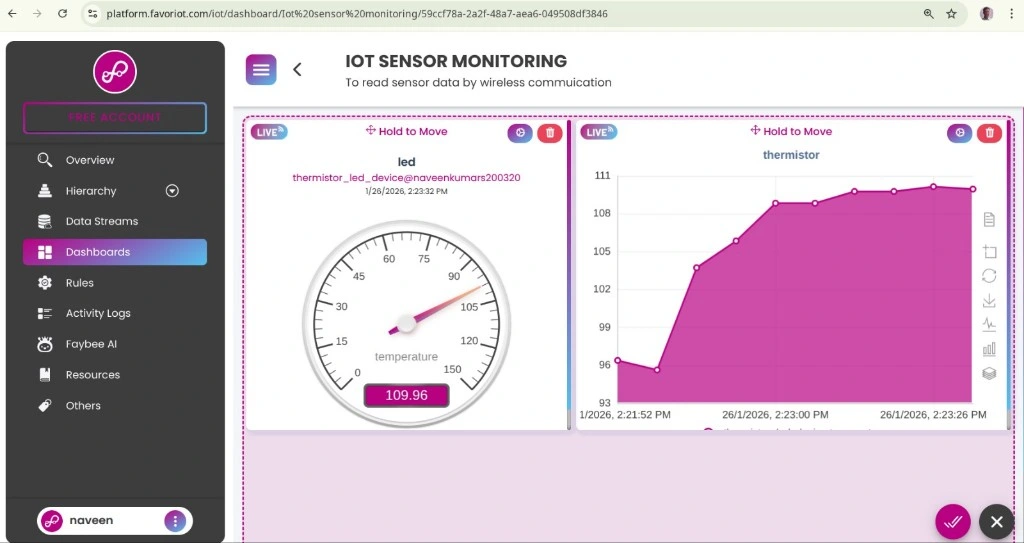

In platforms like Favoriot, this pattern is clear. Solutions that connect easily to existing data pipelines, alerting systems, and workflows are adopted more quickly. Prototypes that only function within a tightly controlled lab environment struggle once introduced to real operations.

Interoperability also reduces risk for customers. They want the freedom to change platforms, add analytics tools, or integrate with enterprise systems without redesigning the entire solution. Flexibility builds confidence, and confidence accelerates adoption.

Clear Return on Investment

The third trait is clarity of return on investment. Customers do not buy sensors for their technical elegance. They buy outcomes.

They want fewer equipment breakdowns, lower operational costs, improved safety, reduced energy consumption, or better regulatory compliance. When an IoT solution clearly links its data to these outcomes, commercial conversations become easier.

Researchers and developers who frame their prototypes around operational pain points tend to move faster toward commercialisation. Instead of presenting features, they present impact. Instead of showing data streams, they show cost reduction, risk avoidance, or productivity gains.

This shift in framing changes how decision-makers evaluate the solution. The technology becomes a means rather than the message.

Aligning Research with Market Reality

Understanding scalability is only half the challenge. The other half lies in how researchers and developers align their work with market needs from an early stage.

One line I often repeat to myself and to teams I mentor is this: your discovery is exciting, but the customer’s concern is practical. This difference in perspective explains many stalled commercialisation efforts.

Go to the Field Early

Laboratory environments are controlled, clean, and forgiving. Real-world environments are not. Weather, dust, vibration, inconsistent power, human error, and unpredictable usage patterns expose weaknesses that no simulation can fully capture.

Researchers who visit deployment sites early gain insights that shape better designs. Talking to farmers, property managers, utility technicians, and facility operators reveals constraints that rarely appear in technical papers.

Testing a device in the rain, inside a metal cabinet, on a vibrating structure, or under intermittent connectivity teaches lessons that influence enclosure design, power management, mounting methods, and firmware behaviour.

These lessons often matter more than marginal improvements in sensor accuracy.

Design for the Maintainer, Not Just the User

Another significant alignment shift is recognising who interacts with the system after deployment. In many IoT projects, the end user is not the person maintaining the device.

Maintenance teams care about access, diagnostics, replacement procedures, and visibility into device health. Accounting teams care about lifecycle costs, not just upfront pricing. Procurement teams care about standardisation and supplier risk.

When researchers design with these stakeholders in mind, their solutions fit more naturally into organisational processes. Documentation improves. Deployment becomes smoother. Support requirements decrease.

Treat Commercialisation as a Discipline

Commercialisation is not an afterthought. It is a discipline that deserves the same rigour as research and development.

This means validating assumptions about power consumption, connectivity costs, maintenance frequency, and operational workflows early. It means measuring performance over time rather than during short demonstrations. It means accepting that simplicity often beats sophistication in market settings.

The most successful IoT solutions I have seen are not the most complex. They are the ones that behave consistently, integrate smoothly, and deliver measurable value without constant supervision.

Closing the Gap Between Research and Scale

Bridging the gap between research prototypes and real-world impact requires a mindset shift. Technical excellence remains essential, but it must be balanced with operational realism.

When researchers build with the environment, the maintainer, and the accountant in mind, their work gains a more straightforward path to scale. When developers prioritise predictability, interoperability, and return on investment, their solutions move beyond pilots and into sustained deployment.

Commercially scalable IoT does not demand less innovation. It requires innovation that survives contact with reality.

Leave a Reply